- June 4, 2025

- Dennis Campbell

- 0

Introduction

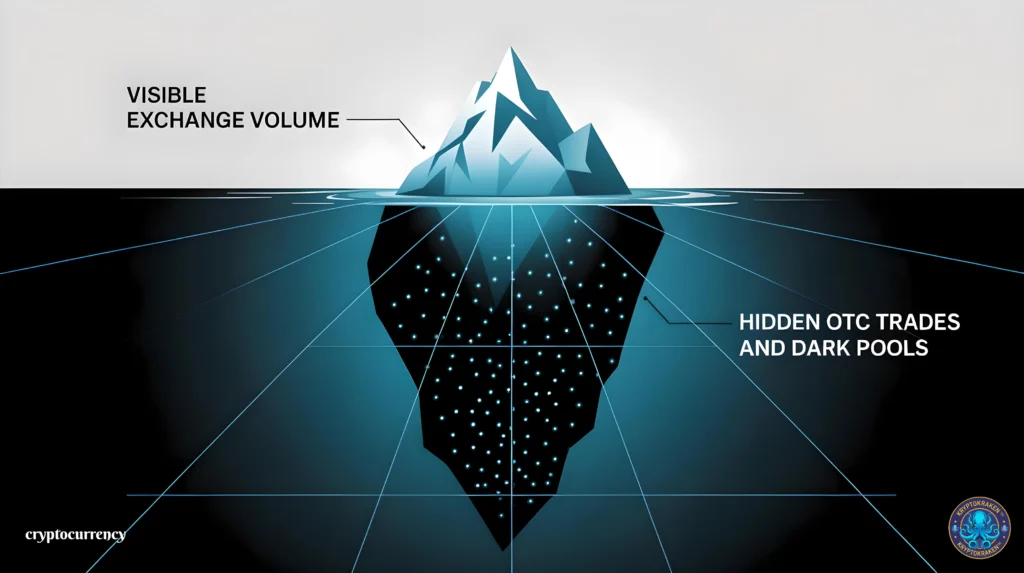

Dark pools – private and anonymous trading venues – have long been a part of traditional finance, allowing institutions to trade large blocks of assets away from public exchanges. In recent years, similar mechanisms have emerged in cryptocurrency markets, raising questions about their impact on price transparency and fairness. This report delves into what dark pools are, how they operate, and how “dark pool-like” trading is used in crypto, with a focus on Ripple’s XRP.

We explore how institutions might quietly accumulate XRP without moving the market, review theories of price manipulation involving XRP (including roles of Ripple Labs, On-Demand Liquidity partners, and whale wallets), highlight real-world examples of large XRP trades that flew under the radar, and compare these practices to Bitcoin and Ethereum. Finally, we consider the implications for retail investors in terms of transparency, price discovery, and institutional advantage.

What Are Dark Pools? (Origins in Traditional Finance)

Dark pools are private exchanges or forums for trading securities that are not accessible to the general public. They emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s as a way for institutional investors to execute large trades (block trades) anonymously without tipping their hand to the broader market. Regulatory changes in 1979 (SEC rule 19c3) allowed off-exchange trading of listed stocks, paving the way for the first dark pool venues by the mid-1980s (Instinet’s “After Hours Cross” in 1986, ITG’s POSIT in 1987).

In the decades since, dark pools grew from handling only ~3-5% of equity volume to a substantial share of trades; by 2017, an estimated 40% of U.S. stock trades occurred off-exchange (including dark pools and other non-exchange venues), up from 16% in 2010.

Why were dark pools created? The primary purpose was to avoid market impact when trading large positions. If a big institution tried to sell millions of shares on a public exchange, other traders would see the order, potentially panic or front-run, and the sheer size could drive the price down before the order filled.

Dark pools allow these large orders to be matched anonymously and discretely, so the price isn’t impacted in the same way. In essence, they offer liquidity with privacy – hence the term “dark” (lack of transparency) versus “lit” public markets. Early dark pools were often run by brokers or consortiums of banks specifically to facilitate trades for mutual funds, pensions, and hedge funds that needed to move size without alerting the entire market.

From a regulatory standpoint, dark pools are typically registered as Alternative Trading Systems (ATS) and are legal and regulated (in the U.S., by the SEC). However, their opaque nature has attracted scrutiny. Trades in dark pools are reported only after execution, often in aggregated form, which reduces transparency in the overall market.

Critics argue this can disadvantage retail investors and distort price discovery, since a significant amount of trading happens “in the dark” before the public sees the volumes. Regulators have at times fined dark pool operators for issues like favoring certain clients or not handling orders as advertised, underscoring the tension between confidentiality and fairness in these venues.

How Dark Pools Work (Order Types, Matching, and Privacy)

In a traditional lit exchange (like NYSE or Nasdaq), the order book is visible – you can see bids and asks and the sizes waiting to be filled. In a dark pool, no such information is visible to participants or the public; orders are hidden and only revealed after they are executed. Typically, institutions will send buy or sell orders to a dark pool (often through their broker or an algorithm).

The dark pool’s system will attempt to match orders internally – for example, matching a buyer and seller at an agreed price, often the midpoint of the public market’s bid-ask spread to be fair to both sides. If a match is found, the trade is executed without ever showing up in the public order book, and the details might only be reported to regulators or via trade reporting facilities with a delay. Other participants in the dark pool generally learn of the trade only after the fact, via “prints” that show the quantity, price, and time, but not who the parties were.

Order types in dark pools can be similar to exchanges (limit orders, etc.), but a common mechanism is the midpoint peg – orders that execute at the midpoint of the national best bid and offer (NBBO) from the lit markets. This way neither side gets worst pricing and the trade remains fair. Some dark pools operate as “crossing networks,” scheduling matches at set times or when compatible orders arrive. Others allow continuous trading like an exchange but without display.

The matching logic prioritizes price and time like normal, but with no displayed liquidity, participants often use feeler algorithms to detect if their orders are likely to find a match (though regulations limit certain abusive practices like pinging for hidden liquidity).

The privacy benefit is huge for institutions: they can buy or sell large blocks without alerting the market and causing sharp moves. Only after the trade is done might the public see a large trade print, which could be minutes or hours later. By then, the institution has finished their business. For example, if a hedge fund wants to quietly accumulate 5 million shares of a stock, doing so in a dark pool means the price on the open market may barely budge, versus the spike that would occur if those 5 million buy orders were on the exchange for all to see.

However, dark pools are not without controversy or regulation. They are indeed regulated (legal ATS venues in the US), but their opacity raises concerns. Some high-frequency trading (HFT) firms have been accused of gaming dark pools – e.g., by submitting small orders to detect the presence of a large buyer or seller (so-called pinging), then trading on that knowledge elsewhere. Regulators have fined dark pool operators for allowing such behavior or misrepresenting how anonymous their pools truly were.

Despite this, dark pools remain popular: they offer lower transaction costs and avoid signaling risk. There are various types of dark pools – some owned by broker-dealers (internalizing their clients’ trades), some by exchanges or independent companies, and even electronic market-maker dark pools. Each may have slightly different rules and participants, but all share the common trait of keeping orders hidden until execution.

Evolution of Dark Pool Mechanisms in Crypto Markets

In the cryptocurrency realm, there aren’t “dark pools” in the strict regulatory sense of an ATS (since crypto markets largely operate outside traditional SEC-style regulation), but analogous mechanisms have evolved. The crypto equivalent of dark pools is essentially over-the-counter (OTC) trading desks, private brokerages, and internal exchange block trades, where large crypto transactions can occur outside of the public order books. These allow whales and institutions to transact big volumes of Bitcoin, XRP, Ethereum, etc. directly with a counterparty or via a broker, rather than placing giant orders on Binance or Coinbase that would instantly move the market.

In the early days of crypto (2012-2016), liquidity was thin and any large buyer/seller had a tough time executing without slippage. This led to the rise of OTC desks – services provided by exchanges (like Coinbase Prime, Kraken OTC) or specialized firms (Genesis Trading, Cumberland, etc.) to match large buyers and sellers privately.

Today, most major exchanges offer OTC or block trading specifically to accommodate institutional clients who want to trade quietly. For example, Coinbase and Kraken have channels for institutions to trade large blocks off the public order book, and there are even decentralized protocols trying to enable peer-to-peer big trades in a private manner. The effect is similar to dark pools: big money players (hedge funds, family offices, even governments) can buy or sell crypto without broadcasting their order to everyone.

Some crypto startups have explicitly branded themselves as “dark pools.” For instance, Republic Protocol (Ren) launched a dark pool for crypto in 2018, and Omega One (proposed in 2017) aimed to build an off-exchange liquidity network. These projects use smart orders and sometimes cross-chain atomic swaps to match large trades without centralized order books. While not all early projects survived, the concept has gained traction as crypto markets matured. By 2024, institutional OTC volumes in crypto had soared – one report noted a 106% jump in institutional crypto OTC volume in 2023, reflecting that big players increasingly prefer private trades for large orders.

A recent notable development is Ripple’s acquisition of Hidden Road, a prime brokerage firm. Hidden Road (now Ripple’s subsidiary) launched OTC crypto swaps for institutional clients in the U.S. in 2025. This service allows institutions to trade large positions in crypto (including XRP) via cash-settled swaps off-exchange, much like a dark pool or OTC derivative. The aim is to serve institutional demand that doesn’t want to (or in some cases, legally cannot) use the wild west of public crypto exchanges.

Hidden Road’s CEO noted that these private OTC swaps constitute a significant portion of global crypto trading volume, yet were largely unavailable in the U.S. until now. With regulatory licenses (FINRA broker-dealer, European MiCA license), Ripple’s move essentially gives it an in-house infrastructure for dark pool-like trading for crypto assets.

XRP-specific mechanisms: Even before Hidden Road, Ripple itself has facilitated institutional trading of XRP outside public markets. Ripple’s quarterly reports often mentioned OTC sales – Ripple had been selling portions of its XRP holdings to institutional partners via OTC since at least 2019. These sales were done in a way that did not flood the open market. In fact, Ripple’s OTC distributions have been structured so as not to depress the market price – even as Ripple moved millions of XRP from its treasury to partners, XRP’s price action often continued to follow broader market trends or even rose. According to one crypto commentator, this practice is “nothing new or specific to XRP” – it’s simply analogous to how equities or FX markets operate, with big players transacting off-exchange when needed.

Another mechanism in the XRP ecosystem is On-Demand Liquidity (ODL), Ripple’s solution for cross-border payments. ODL uses XRP as a bridge currency between fiat pairs. Technically, ODL transactions happen on exchanges (buying XRP in one country, transferring, then selling in another) – but Ripple has often been in the background supplying liquidity to ODL partners through OTC arrangements or structured sales.

Ripple has claimed that these ODL-related XRP flows do not influence market price, since they try to match them with real demand for payments. Whether or not that’s entirely true, it suggests that Ripple coordinates large XRP movements in a way that’s more closed-door than open market. ODL transactions are typically split into many small chunks to avoid slippage, or done via partner liquidity providers, effectively acting like mini dark pool executions embedded in payment flows.

It’s worth noting one popular community rumor: the idea of a “private XRP ledger” or exclusive dark pool where XRP trades at vastly higher prices (figures like $100,000 per XRP have been thrown around in fringe discussions). This theory posits that institutions or banks are secretly transacting XRP on a parallel ledger at enormous valuations while the public market lags.

However, this has been debunked by experts. Ripple’s CTO David Schwartz and others have clarified that XRP only exists on the public XRP Ledger – there isn’t a separate hidden price for “real” XRP. While Ripple has run private ledgers for central bank digital currency tests, those are more like simulations or permissioned networks and not a separate market for XRP value. As one analyst put it, why would an institution pay $10,000 for XRP “on a private ledger” when it’s $2 on the open market? They wouldn’t – instead, they accumulate OTC at market prices or slight discounts, not exorbitant premiums.

In fact, history shows Ripple gave institutional buyers discounts (for example, in a deal with R3, an option to buy XRP at fractions of a penny) – far from selling at sky-high secret prices. In short, the dark pool activity around XRP isn’t some alternate universe of crazy prices; it’s about quietly trading at the same price, just out of public view.

How Institutions Accumulate XRP Without Moving the Market

Imagine an institution or large investor wants to acquire a huge amount of XRP – say 500 million XRP (half a billion) – but they don’t want to drive up the price while doing so. If they placed a buy order of that size on a public exchange, the effect would be immediate: the buy wall would consume all available sell orders and send XRP’s price skyrocketing in seconds. Everyone in the market would notice a sudden spike and likely FOMO (fear of missing out) would kick in among retail traders. To avoid this, institutions use stealthy methods: OTC desks, private swap agreements, or coordinated buys via multiple exchanges (“slicing” the order). This is essentially the crypto version of dark pool accumulation.

For example, reports from XRP community analysts describe how a firm like BlackRock (hypothetically) could accumulate 1 billion XRP through non-public channels. Instead of one giant public buy, they might arrange through an OTC broker to find sellers off the books. The OTC broker might source XRP from other whales or even from Ripple’s treasury in tranches, matching the buys and sells internally. These transactions are not visible to the public in real time – they might only appear later as large transfers on the blockchain (e.g. moving from the broker’s wallet to the institution’s cold wallet) once completed. By then, the accumulation is done at negotiated prices, and the market price barely flinched during the process.

XRP whale holdings (grey area, addresses with 100M–1B XRP) versus XRP price (green line) during April 2025. The chart shows large holders selling off XRP as the price dipped and then rose, illustrating how whale activity often runs counter to visible market trends. Such behind-the-scenes moves can suppress or delay price reactions.

As the above chart suggests, whales and institutions can significantly influence XRP’s supply-demand dynamics without obvious signals on exchanges. In early April 2025, for instance, on-chain data showed that whale wallets holding 100 million to 1 billion XRP were quietly dumping a total of 370 million XRP (worth around $700+ million) over a couple of weeks. During this period, XRP’s price actually fell to a local low and then began climbing to over $2, but the public order books didn’t immediately reveal why.

Only by looking at wallet data (through Santiment analytics) did it become clear that major holders had distributed a huge amount of XRP, likely keeping the price from rising faster. Such distribution could be done via OTC deals or coordinated selling on multiple small exchanges to avoid a single large dump that would crash the price. The end result is price stability (or stagnation) in the public eye, even while big transfers occur in the background.

On the flip side, there’s evidence of quiet accumulation as well. Over roughly the same timeframe (April to May 2025), wallets holding 10–100 million XRP (slightly smaller whales) accumulated about 900 million XRP according to Santiment data. That’s nearly half a billion USD worth added by large players without igniting a massive rally – again indicating it was done strategically. Analysts noted this surge in whale holdings aligned with a modest price uptick of about 4-5% during those weeks, nothing too dramatic, which suggests the buying was spread out and often off-market. Institutional buyers often prefer to accumulate gradually and through dark channels so that they don’t “show their hand” and cause others to front-run or jack up the price.

This pattern is not unique to XRP. In Bitcoin and Ethereum, we see similar behavior: for example, in June 2025, a whale (or institution) purchased 108,000 ETH (around $283 million worth) via Galaxy Digital’s OTC desk rather than on open exchanges. The broker withdrew tens of thousands of ETH from exchanges in batches and transferred the total to the client’s wallet, all while ETH’s price stayed relatively stable around $2,626. Only later did observers piece together that an enormous buy had occurred off-market.

Such moves increase scarcity (removing coins from circulation into long-term holdings) without the immediate spike that a comparable buy on, say, Coinbase would have caused. It’s a classic example of whales buying without pumping the price – precisely the advantage dark pools and OTC give them.

In summary, institutions accumulate XRP in stealth mode by using dark pool-like strategies: splitting orders, using OTC intermediaries, timing transactions during low-volatility periods, and even direct deals with entities like Ripple. The accumulation is often masked as a series of normal transfers or is entirely off-ledger until settlement. To an ordinary retail trader, the price may appear flat or only slightly up, giving the impression that there’s “no big interest,” whereas in reality large players are loading up behind the scenes.

Theories of XRP Price Suppression and Coordinated Activity

The secretive accumulation and distribution of XRP has led to various theories about price suppression. Many XRP holders have wondered: with all the positive developments (Ripple’s tech adoption, legal victories, etc.), why does the price remain relatively flat or subdued? Some point to dark pool activity as an answer: institutions and possibly Ripple itself keeping the price in check until a future point.

One theory argues that sophisticated players intentionally suppress XRP’s visible price through off-market accumulation – essentially a deliberate phase of quiet accumulation before an explosive move. Pseudonymous XRP analysts on social media have detailed how bots and algorithmic traders often dominate the public order books, creating a facade of regular trading while true accumulation happens in the shadows. They claim that dark pools and private deals are used to hide large buys, preventing the typical supply squeeze that would drive up price. As a result, the market price is “artificially” suppressed – it doesn’t reflect the actual long-term demand, because much of that demand is being filled off-exchange without bidding against retail orders.

Proponents of this view often note that XRP’s supply on public exchanges has been dropping to historic lows while big players stash XRP in private wallets. For example, if Ripple’s On-Demand Liquidity partners or other institutions are buying directly from Ripple or via OTC, those XRP never really sit offered on exchanges. Retail traders see low volume and a stagnant price and assume there’s little interest, whereas in reality tons of XRP have changed hands in private.

One analyst described it as “an invisible force holding prices stable” despite growing institutional interest. As long as those private channels can source liquidity, the public price won’t shoot up. But the theory posits that eventually, when the off-market supply is exhausted, any new demand will have to hit the public exchanges, and that’s when price could violently correct upward. In other words, a spring coiled by suppression eventually boinging free – or as one XRP researcher put it, a pot boiling over after simmering too long once demand overtakes the quietly diminished supply.

Another aspect of these theories involves Ripple Labs’ own role. Ripple holds a large trove of XRP (billions in escrow) and releases a controlled amount each month. Some skeptics suggest Ripple could strategically sell into any rally or otherwise manage its escrow releases to cap the price below a certain level. There have been claims that Ripple’s monthly escrow sales and a few known large XRP wallets correlate with XRP price drops, implying coordinated selling when price tries to run. Notably, community researchers identified certain wallets (not officially confirmed as Ripple’s) that tend to send XRP to exchanges before or during price rallies, adding supply and potentially tempering upward momentum. This has fueled speculation that someone (Ripple or aligned stakeholders) prefers XRP to remain in a stable range until broader adoption is ready.

Specific evidence cited includes observations like: in late 2022 and 2023, Ripple was buying back XRP from the open market at times, and also selling more during other periods, seemingly to stabilize price. One researcher used Ripple’s own API to track its XRP sales/purchases and found that Ripple ramped up sales when price was high, and even bought back about 500 million XRP when price was low – effectively acting to smooth out volatility. He concluded that Ripple might be “trying to keep the price as stable as possible”. Indeed, Ripple’s Q3 2022 quarterly report openly stated the company has been a buyer of XRP in the secondary market and will continue buying as ODL (utility) grows. They also noted they only sell XRP in connection with ODL transactions and had ceased all programmatic open-market sales since late 2019.

This suggests that Ripple is managing XRP distribution in a controlled way – not dumping willy-nilly, but injecting or removing liquidity to support their payments network growth. While Ripple would frame this as fostering healthy markets (preventing wild swings that could hamper XRP’s utility), some in the community see it as a form of price control – a coordinated effort to prevent XRP from either crashing or mooning too fast.

There are also more conspiratorial takes. One theory floated by an analyst was that major financial institutions (“big banks”) intentionally spread negative sentiment or keep XRP prices low while accumulating it cheaply, anticipating future utility. This overlaps with the general idea of quiet accumulation: the notion that those in the know want to load up on XRP at $2 quietly because they believe it will be worth much more once banking adoption, regulatory clarity, or other catalysts hit. It does sound a bit like a spy novel – banks colluding to suppress a digital asset’s price – and as the analyst admitted, it’s mostly speculation without hard proof. But the reason such theories persist is the observable phenomena (flat price, shrinking exchange supply, whale movements) combined with the somewhat opaque actions of Ripple and partners.

Crucially, none of these suppression theories have been conclusively proven. They remain educated guesses based on circumstantial evidence. XRP’s price stagnation through certain periods can be explained by many factors, including the multi-year SEC lawsuit that dampened U.S. trading and general market cycles. In fact, when that overhang was lifted (Ripple’s partial legal win in mid-2023), XRP’s price did jump initially – but then leveled off, which brought renewed attention to the idea that something else was holding it back.

Real-World Examples: Whale Moves and Suspicious XRP Trading

To illustrate how dark pool-like trading might be affecting XRP, let’s look at some real-world large XRP transactions and patterns:

Ripple’s Escrow Locks/Unlocks: Ripple’s management of its 55 billion XRP escrow is a transparent but significant mechanism. Each month, 1 billion XRP is released; Ripple sells or uses some portion and re-locks the rest. In May 2025, Ripple surprised observers by locking 700 million XRP back into escrow in one go (three transactions of 500M, 170M, 30M XRP) – outside the normal monthly schedule. This was worth $1.5+ billion, locked within minutes. Such a move reduced circulating supply suddenly, signaling that Ripple did not intend to sell those tokens soon. Analysts speculated Ripple did this to bolster market confidence (assure investors they won’t flood the market) and possibly to prepare for something like a potential XRP ETF or new partnerships.

The timing – during a period of price stagnation – fueled talk that Ripple might be intentionally constraining supply to set the stage for a future price breakout. Regardless of intent, this incident shows Ripple’s unique ability to remove a huge amount of XRP from availability with the push of a button, a lever not many projects have. It’s not a dark pool trade per se, but it’s a form of supply-side coordination that can affect price indirectly by controlling float.

Whale Alert transfers: The blockchain’s transparency means every large XRP transfer gets noticed by services like Whale Alert. Throughout 2023-2025, there have been many Whale Alert reports such as: “200,000,000 XRP transferred from Ripple to unknown wallet”, or “100M XRP moved from an unknown wallet to exchange”. For example, in April 2025, Whale Alert noted a transfer of 131 million XRP (over $270 million) between two unknown wallets. Such big moves often set off community chatter: is someone accumulating or prepping to sell? In one case, on April 15, 2025, a whale moved 70 million XRP (worth ~$150 million) into Coinbase, presumably to sell given it’s an exchange deposit. Indeed, shortly after, XRP’s price saw downward pressure.

These kinds of moves show coordinated activity by large holders – whether it’s one entity or several is sometimes unclear, but the pattern of moving tens of millions of XRP in single transactions suggests strategic intent (either an OTC deal settlement, an exchange sale, or a custodial reshuffle). When multiple such transfers cluster in time, it hints at whales acting in concert or responding to the same signals (e.g. an upcoming event like the SEC case resolution, where some might have sold the news).

Whale accumulation patterns: Conversely, there are periods where Whale Alert will report large XRP being scooped up off exchanges. An example: November 2024 saw a string of alerts as an unknown wallet kept buying 5–10 million XRP from various exchanges over weeks, totaling close to 100M XRP acquired. On-chain sleuths tied this wallet to a probable institutional custodian. Over that period, XRP’s price barely moved around the $1.20 mark. It later came out via Ripple’s quarterly report that an “institutional buyer” had been active – likely facilitated by Ripple’s OTC channels. This is exactly how stealth accumulation manifests: instead of one big buy, it’s lots of medium buys spread out, often masked through different exchanges or wallets, so no single spike betrays the whole plan.

Santiment analytics (whale tiers): Blockchain analytics firms categorize holders by size. Santiment charts have shown interesting dynamics among different whale tiers. For instance, addresses with 1M–10M XRP might be increasing holdings while the 10M–100M group is decreasing, or vice versa. In April 2025, as mentioned, the largest whales (100M+ tier) were selling, while the smaller whales (10M-100M tier) were buying.

This could indicate internal rotation (biggest players offloading to eager smaller institutions) or simply different strategies (some whales taking profit, others accumulating for long term). Either way, these shifts happened largely off the visible order books, evidenced by the fact that prices didn’t swing wildly during the transfer of hundreds of millions of XRP. It’s the on-chain equivalent of dark pool prints – you see the result (wallet balances changed) after the fact, but you didn’t see the trade execution live on an exchange.

Ripple’s ODL volumes: Ripple’s On-Demand Liquidity flows deserve mention as “quasi-dark” volumes. At its peak, ODL was moving billions of XRP through partner exchanges for remittances. These transactions are real and show up as volume, but they are not speculative trades – they are programmatic conversions for payments. Ripple has at times routed ODL traffic strategically to certain exchanges to manage liquidity.

Some have speculated Ripple could even pause or throttle ODL transactions if the XRP price starts running too hot, to avoid slippage (since ODL buys XRP as part of its process). That kind of coordination – using utility flows as a damping or boosting mechanism – is hard to verify externally. Yet Ripple did note that ODL-related purchases were the only sales they were doing, implying they closely control those operations to not disturb the market. In effect, Ripple and its ODL partners act as their own dark pool, matching cross-border payment demand with XRP liquidity largely outside of retail trading.

Summing up the examples: we see a constant dance of large XRP movements that are often invisible until after they occur. Whales and Ripple regularly move nine-figure sums of XRP around in ways that avoid spooking the market. Sometimes this looks like suppression (big selling into rallies), other times like strategic accumulation (big buying without rallying). For an average retail holder, these activities can be frustratingly opaque – you wake up to find out an entity quietly sold $100M of XRP last week and you never saw it coming because the price barely twitched.

Counterarguments: Market Forces and Transparency Concerns

It’s important to note that not everyone agrees that XRP’s price is being actively “suppressed” by shadowy forces. Skeptics of the suppression theories point out that much of the evidence is circumstantial. For instance, attorney Bill Morgan has addressed these claims directly and provided some grounded context. He notes that while Ripple holds a large amount of XRP, it doesn’t have as much control as some think.

For one, Ripple’s share of total XRP supply is often overstated. It’s commonly cited that Ripple holds ~43% of supply, but Morgan clarifies that if you exclude the XRP locked in escrow and count only circulating supply, about 58.5% of XRP is in public hands (CoinMarketCap data). Ripple’s actual immediate influence is mainly through the monthly escrow releases, which, as he highlights, amount to less than 1% of total XRP trading volume each month.

Indeed, Ripple’s sales (net of purchases) in recent quarters have been a few hundred million XRP, whereas XRP’s monthly trading volume on global markets is tens of billions of XRP. Such a small percentage is unlikely to meaningfully suppress price on its own. Additionally, Morgan points out that as time goes on, Ripple’s impact via escrow diminishes – because circulating supply grows and markets become more liquid, the same 1B/month (if fully sold, which it isn’t) is a smaller fraction of the pie.

Crucially, the SEC’s investigation into Ripple (2018-2020) found no evidence of XRP price manipulation by the company. The SEC was certainly no friend to Ripple, suing them for unregistered sales, but even with subpoenaed internal documents and years of market data, the SEC did not claim Ripple was scheming to suppress or pump price – only that they sold XRP as an investment contract. In that lawsuit, Ripple even presented expert evidence that XRP’s price largely follows the broader crypto market (especially Bitcoin and Ethereum) rather than being driven by Ripple’s actions.

This undercuts the idea of a grand conspiracy holding XRP down; one might expect if Ripple or associates were actively manipulating the price, some red flag would have appeared in that intense legal discovery process.

From a market structure perspective, one can argue that what’s interpreted as “suppression” might simply be normal market forces in a highly liquid asset. XRP, being in the top 5 by market cap, trades on dozens of exchanges worldwide. If big institutions are buying OTC, those coins still eventually come from somewhere – likely from sellers who might otherwise have sold on exchanges. So the net effect on supply-demand may not be so mysterious: large buyers absorb selling pressure off-exchange, which keeps the exchange order books balanced. Rather than calling it suppression, one could call it efficient execution. The price stays flat because the market has found equilibrium: new demand (even institutional) was matched by available supply at the current price.

In other words, just because price is flat doesn’t mean it’s artificially suppressed; it could mean the market is accurately pricing in all known information plus the stealth accumulation. The “spring coiling” theory only holds if one assumes latent demand far outstrips supply – something not guaranteed until it actually happens.

That said, even the skeptics acknowledge some issues of transparency and fairness. Dark pool or OTC activity by definition means retail investors are in the dark until after the fact. A newcomer looking at XRP’s trading volume and order books might not realize that huge deals are happening behind the scenes. This asymmetry in information can favor insiders or those with access to analytics. It also means price discovery is potentially less efficient – the publicly traded price might lag actual sentiment or value because so much trading is hidden. Retail traders might chase false signals; for example, seeing a low volume consolidation and thinking interest is low, when in reality whales are accumulating for a big move.

For retail investors, the implications are twofold: First, patience and due diligence are key. If the theories are right, then one day the suppression will lift and price will react violently upward – but trying to time that is perilous. It could be months or years, and there’s no guarantee. In the meantime, reacting to every small price move might be exactly what the sophisticated players want (to shake out weak hands).

As some XRP pundits advise, focusing on fundamentals (network growth, utility adoption, regulatory progress) and monitoring on-chain metrics might give a better read than staring at short-term price charts. Second, retail investors should be aware that institutions have an edge in execution. They can buy without pumping the price and sell without crashing it, thanks to private channels. Retail traders typically cannot. This means chasing whale moves is tough – by the time you see evidence that a whale accumulated, it’s too late for you to have bought at those levels; by the time a whale’s distribution hits exchanges and affects price, it’s often after they’ve finished selling.

In traditional finance, this disparity is debated heavily. Dark pools bring liquidity but also raise concerns around transparency and market integrity. In crypto, it’s similar but with even less oversight. The upside is that big institutional flows can be absorbed without extreme volatility (arguably a good thing for a nascent asset looking to be a stable currency). The downside is an uneven playing field, where big players can operate unseen and potentially even coordinate (though illegal collusion is hard to prove) to the detriment of smaller investors.

Comparison to Bitcoin and Ethereum Practices

To put the XRP situation in context, it’s helpful to note that Bitcoin and Ethereum also see large-scale OTC and dark pool-like trading. The concept of whales quietly accumulating or distributing is not unique to XRP at all. In fact, Bitcoin probably has the most developed global OTC market – miners, early adopters, and institutions routinely transact huge blocks of BTC off-exchange. For instance, throughout 2020 and 2021, as institutions like MicroStrategy and Tesla were buying Bitcoin, they explicitly used OTC brokers to avoid slippage. MicroStrategy’s CEO Michael Saylor described how they would break up buys into small pieces and execute via algorithms across multiple dark pools and trading platforms so as not to telegraph their intent and spike the price on themselves. The result was that MicroStrategy accumulated over 100,000 BTC within months, and while their announcements did tend to bump the price, the actual buying process was quite stealthy.

Ethereum likewise has OTC accumulation – the earlier example of 108k ETH bought via Galaxy Digital’s OTC desk in 2025 shows that even multi-hundred-million-dollar positions can be acquired with minimal market stir. And when large holders want to exit positions, they often do so in negotiated deals (e.g. an ETH ICO treasury unloading via OTC to a fund rather than market selling and crashing the price).

In July 2023, it was reported that a single whale moved 50k ETH to Coinbase (presumably to sell), but simultaneously another whale was withdrawing a similar amount from Coinbase – suggesting an OTC arrangement brokered through the exchange where one big holder sold directly to another via the exchange’s internal systems. This is analogous to a dark pool match – the public order book didn’t show a 50k ETH sell wall; it happened in the background and only wallet movements gave clues.

One difference is that Bitcoin’s supply is more decentralized (no single entity like Ripple controlling a large chunk). So manipulation theories for BTC often revolve more around exchanges and leveraged products (e.g. whales shorting futures while selling spot OTC to push price, etc.) rather than a foundation dumping tokens. Ethereum’s supply is also not centrally controlled, though the Ethereum Foundation and early whales have large holdings. Still, accusations of price suppression occur in those communities too, often citing OTC flows or coordinated selling around certain events. For example, some analysts warned that the launch of Bitcoin ETFs led to whales offloading BTC in anticipation, largely through OTC deals that were only noticeable when prices failed to rise as expected.

In terms of dark pool infrastructure, there have been attempts to create more formal dark pools for Bitcoin and Ethereum trading. NASDAQ reportedly discussed opening a crypto dark pool for institutional clients, and there are fintech companies offering “liquidity pools” where only vetted investors can trade large blocks of BTC/ETH at agreed prices out of public view. These haven’t gone fully mainstream yet, partly due to regulatory hurdles, but they indicate the demand.

Overall, what’s happening with XRP is not an isolated phenomenon but part of a broader pattern: as crypto matures, the trading behavior of large players is starting to resemble that in traditional markets. The presence of hidden liquidity and private deals is a sign of institutional involvement. Bitcoin, Ethereum, XRP – all are seeing the tug-of-war between transparency (what’s on-chain or on exchanges) and opacity (what’s happening in bilateral channels). For retail holders of any coin, the lesson is that not all volume is visible and not all price drivers are obvious in real time.

Implications for Retail Investors and Market Health

The rise of dark pool-like trading in crypto, and specifically the behind-the-scenes action in XRP, carries several implications for regular investors:

Transparency and Trust: Crypto was founded on principles of transparency (every on-chain transaction is visible) and equal access. Dark pools introduce an element of opacity that can undermine trust. If retail investors feel that “the real action” is happening where they can’t see or participate, they might feel discouraged or that the market is rigged against them. It’s important for projects like XRP (and exchanges serving them) to be as open as possible about volumes and perhaps provide aggregated data on OTC trades.

Some exchanges do publish block trade details or at least incorporate them into overall volume metrics. But currently, it’s tough for an average person to gauge how much XRP is being bought by institutions off-order-book. This opacity can lead to mispricing or surprise volatility – e.g. if a huge buy or sell has been completed privately, the market could move sharply once that information eventually surfaces or if the participants then adjust their exchange positions.

Price Discovery: Dark trades mean that price discovery is fragmented. The public market price of XRP is based on relatively smaller trades and algorithmic market-making, while big fundamental moves might be happening off-market. This can lead to a disconnect – some argue XRP’s price doesn’t reflect its “intrinsic value” or the scale of institutional interest. Only when those private sources either run dry or overflow into public markets will price catch up. For retail investors, this means standard technical analysis or market indicators could be less reliable. Volume spikes, order book depth, etc., might not tell the full story if half the volume is in dark pools. Investors might need to supplement with on-chain analysis (watching whale wallet counts, exchange inflows/outflows) to get a clearer picture of supply and demand.

Institutional Advantage: It’s clear that institutions have tools at their disposal that individuals do not. They can hire OTC brokers, use algorithms that slice orders across dozens of venues, and have the patience to accumulate over weeks or months unseen. Retail traders often operate with much smaller size and on a single exchange at a time, so they simply cannot replicate these stealth tactics. This asymmetry means institutions can enter or exit positions with far less slippage and often with better average pricing than a retail trader trying to buy the same amount over the same time.

Essentially, big players can avoid the market impact cost, while small players bear it (when a retail trader hits “market buy” for a large amount, they eat through the order book and move price against themselves; an institution rarely does that). The presence of dark pools accentuates this disparity. For the market to remain fair, it’s important that abuses are monitored – e.g. if institutions were using dark pools to secretly collude or manipulate (say, two parties pre-arranging trades to paint a tape), that would be concerning.

Regulation and Future Outlook: Regulators may eventually turn attention to crypto dark pools. Thus far, the focus has been on exchange regulation, token legality, etc. But if crypto markets get systemically important, regulators might demand more reporting of large trades, or impose rules similar to equities (e.g. trade reporting requirements even for ATS). Paradoxically, increased regulation could both legitimize and limit dark pools in crypto. For XRP, which sits at the intersection of crypto and banking, any move toward institutional adoption will likely involve more, not less, private trading. Banks and fintechs using XRP for liquidity will prefer stable prices and may coordinate liquidity behind closed doors. Retail investors could benefit indirectly (as it could reduce volatility and spread), but they might feel further removed from the “real” market.

Market Reactions and Strategy: From an investment strategy perspective, knowing that dark pool accumulation is a factor might encourage retail holders to think long-term and fundamentally. If indeed major players are positioning quietly, the “smart money” might be betting on future price appreciation – a bullish sign if you believe they have insight or will eventually drive price up. However, one should be cautious not to follow every rumor. Verified data like exchange reserve drops, whale address growth, etc., are more useful than fanciful claims of secret $100k XRP deals (which, as we covered, have been refuted).

In conclusion, the presence of dark pools and private trading in XRP markets is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it provides the plumbing for large institutional adoption – big transactions can happen without blowing up the price, which is actually good for XRP’s usability as a liquidity tool (no one wants a payment currency that doubles in price overnight because a bank bought some).

On the other hand, it challenges the ideal of an open market accessible equally to all participants. Retail investors should be aware that the XRP market they see on exchanges is only part of the picture. Much like an iceberg, there’s a lot beneath the surface. Staying informed through on-chain analytics, following Ripple’s quarterly reports (which detail sales and purchases), and watching whale activity can offer some glimpse into that hidden portion. Ultimately, if XRP achieves the institutional adoption Ripple is aiming for, we might expect its trading to increasingly resemble traditional FX markets – heavy on OTC and interbank flows – which will require a mindset shift for crypto traders used to transparent order books.

For now, the story of XRP’s dark pools remains one of intriguing possibilities and cautious optimism: institutions quietly accumulating a digital asset while retail holders wait for the day the floodgates open. Whether that day comes suddenly or gradually, being knowledgeable about these behind-the-scenes dynamics is crucial for anyone involved in the XRP market. As always, investors should combine this knowledge with prudent risk management – because in crypto, even the whales and institutions don’t always get it right, and unexpected forces (regulatory changes, macroeconomic swings) can upend the best-laid accumulation plans.

Article Sources:

Ripple Q3 2022 XRP Markets Report (ripple.com); Cointelegraph “Ripple’s Hidden Road debuts OTC crypto swaps in the U.S.” (2025-05-28); Cryptopolitan “Whales accumulated over 880 M XRP in the past month” (2025-05); TradingView/NewsBTC “Ripple whale activity surges—$273 million XRP transfer” (2025-04); SEC v Ripple Labs Inc. complaint PDF (SEC.gov, 2020-12); Binance Square/The Block report “Crypto OTC trading volume surges 106% in 2024” (2025-02); TheCryptoBasic “Galaxy Digital OTC moves 108 278 ETH worth $283 million to whale address” (2025-06-04); Bill Morgan tweet thread on Ripple escrow-price impact (Twitter, 2025-04); CFA Institute policy brief “Non-exchange trading reaches 40 % of U.S. stock volume (spring 2017)”; Investopedia “Alternative Trading System (ATS) Definition and Regulation”; Investopedia “An Introduction to Dark Pools”; Wall Street Journal “Ripple to acquire credit network Hidden Road for $1.25 billion” (2025-05); Whale Alert blockchain transaction feed (e.g., 131 M XRP transfer, 2025-04); Santiment on-chain analytics dashboards (XRP whale tier accumulation/distribution, 2025-04).

This article is in part written with an AI copilot and is not financial advice. Remember to always do your own research and talk with a financial advisor.